The rapid spread of COVID-19 and the resulting confinement of people to their homes has changed the operating environment for many industries, including offshore oil and gas. Some platforms have reduced their headcount by up to 40% and deferred projects, modifications and shutdowns. While this strategy can work in the short term, it could lead to an unmanageable maintenance backlog and an inability to meet regulatory requirements.

Can remote technology help alleviate the increase in maintenance backlog and improve uptime?

Factors affecting maintenance backlog

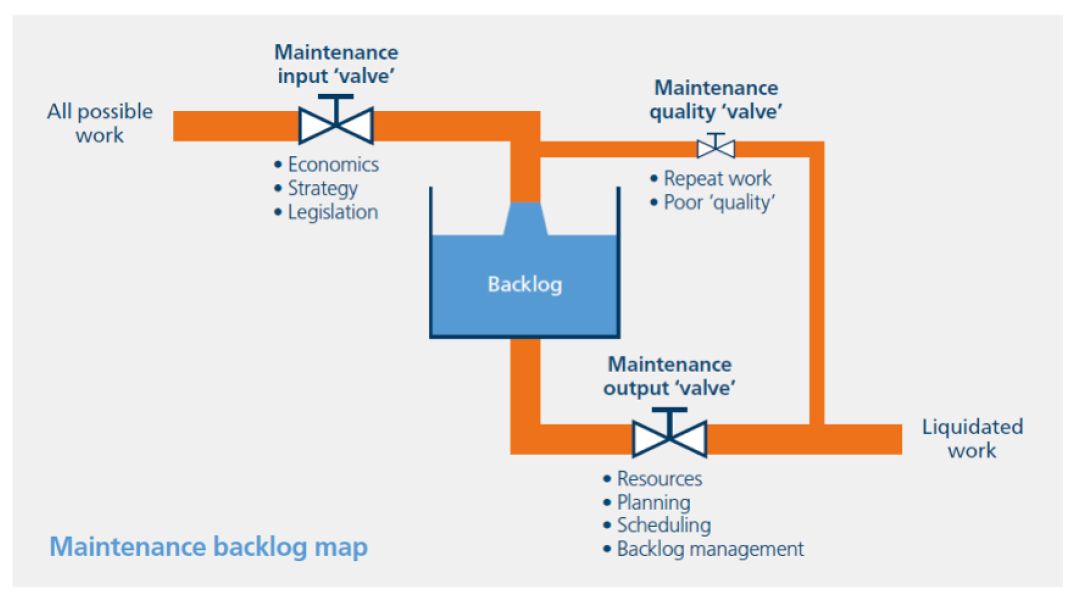

The following diagram describes a typical maintenance system:

The input valve represents all maintenance tasks, including regulatory requirements and vendor recommendations. This "fixed" workload usually stays relatively constant throughout a platform's life, even if other factors like headcount or capacity change. The output valve represents the capacity of the maintenance department. Most work is liquidated, but a small percentage may require rework due to quality of spares or workmanship.

We conducted a poll during our recent webinar that interestingly revealed 48% of respondents felt that their maintenance program could be optimised by 50% or more. At the same time, only 27% of respondents use "a lot" of remote technology, while the rest use "none" or "some". This surprised me because remote capabilities have existed for some time now and are accepted technologies; however, it may be that the incentive or value opportunities remain to be fully realised.

Is the work necessary?

Our experience shows that up to 30% of work generated from a Computerised Maintenance Management System (CMMS) is sub-optimal.

In one case study, a company operated 7 offshore platforms with an operating expense $100 million and 390,000 hours of maintenance activity per year. Lloyd's Register worked together with the client to optimise their maintenance program. The team achieved savings of $22 million and 74,000 hours per year.

There are several areas where maintenance tasks can be optimised or eliminated. One clear example is the case of intelligent instrumentation. These devices have advanced self-diagnostic and self-maintaining features, but most CMMS schedules still include manual routines and checks. This strategy wastes the investment in smart technology and burdens the maintenance department unnecessarily.

Can the work be done remotely?

Advanced Collaboration Environments (ACE) already mirror the platform control room in onshore environments. However, there is potential for much more extensive use of remote technology. For example, digital inspection allows core personnel to take pictures and capture measurements electronically. These can be examined by experts onshore eliminating the need to visit the platform. Wearable tech, like hardhats and safety glasses with embedded cameras, can transmit real-time imagery onshore for immediate analysis and advice.

Condition monitoring uses equipment health measurements like vibration, along with process measurements, to identify a potential failure. Using this information, maintenance teams can plan a repair before excessive damage occurs and avoid breakdowns. Usually, condition monitoring specialists perform their analysis on offshore platforms. But most of their raw data is available or could be made available digitally. This entire function could be performed without specialists travelling to and from an offshore platform.

Are specialist vendors necessary?

Specialist equipment vendors are those that have a specific set of skills or qualifications not ordinarily present in the 'core crew' - those on the platform all the time. This tends to relate to specific or complex equipment. The dependence of offshore platforms on specialist support is high, but this philosophy is seldom questioned.

Nevertheless, an evaluation of specialist workscopes reveals a large number of tasks which are not specialist in nature. Many of these tasks could be performed by core personnel, thus reducing the presence and costs of specialists on an offshore platform. EX inspections and condition monitoring tasks are two prime examples where core personnel can perform the bulk of the tasks without the need for specialist support.

In summary, there's no denying that remote technology can drive maintenance and uptime improvement. The challenge seems to be adopting these technologies into everyday working practices. Will the effects of COVID-19 on operational models change 'post COVID-19', or as an industry will we place more emphasis on utilising remote presence solutions? We perhaps still have a long way to go to close that gap, but I'm hopeful in six months' time if we ran the survey again, we'd see 40% of respondents use "a lot" of remote technology and then perhaps in a year adoption levels may hit 50-60%.